2.6.3 The External Social Structure -

Between Church and Synagogue

Various social entities appear crucial for the movement's external social structure.

Firstly, the individuals of the Israeli public are the defined goal of evangelization. Evangelization aims at the redemption of the individual, but finally and accumulative also at the redemption of the nation (Saperstein 1992: 2-5). Evangelization is an effort to invite individuals to accept the redeeming quality that believers ascribe, to Jesus' sacrificial death, his empowering resurrection and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit (Stern 1991a).

While the movement is not a political movement, the scope of redemption of the whole nation nevertheless gives it a certain political dimension. I could not discern conscious political intents within the movement. The grade of organization of the movement as a whole appeared low and spontaneous, sometimes even only „sporadically and loosely connected” (Martin 1992: 153), not hierarchical (Duyvendak 1992: 12).

Duyvendak ascribes a primacy of politics to social movements. He defines social movements as coherent series of happenings produced in interaction with opponents and carried by a network of actors with political goals who mostly employ non-institutional means (Duyvendak 1992: 14). To me, the movement appeared not constituted by a coherent series of happenings, but as culturally structured clusters of actors, who neither claimed obvious political goals nor seemed restricted to non-institutional means. Some groups of the movement registered organizations and structurally employ institutional means. Nevertheless, comparing the movement with the three types of social movements that Duyvendak distinguishes may be beneficial partially:

- Because instrumental movements pursue goals external to the movement, possibilities of success, reform or threat appear crucial, while action is no goal in itself (Duyvendak 1992: 23). The evangelization of individuals and national redemption can be regarded as external goals of the movement. For neither the individuals to evangelize nor the nation as a whole are yet part of the movement. Neither success nor reform appears predominantly important in the movement, and evangelization appears as a goal in itself, carried out despite success and failure, recognition or opposition.

- Because sub-cultural movements pursue a politics of identity, to distinguish themselves from others, without great expectations towards their political environment, they do not much depend on it (Duyvendak 1992: 24-25). In evangelization the identity as Jew and believer in Jesus gets employed and reaffirmed simultaneously. Since the movement expects from the authorities protection of its religious freedom, an attempt to criminalize evangelization (CWI 1997: 12) must appear life-threatening and cause mobilisation (Duyvendak 1992: 25).

- Counter-cultural movements differ from sub-cultural ones in three respects. First, they depend on abstract and external goals to criticise authorities. Secondly, repression must not lead to defensive position but can serve to denounce authorities. Lastly, repression can serve to reaffirm the own position and that the system is resistant to reform (idem). The movement wants no conflict with the authorities at all, but its protection instead (Taylor 1995). It received recognition in as far as its cases where repeatedly discussed in Knesset and treated in the public by the media. Since legal attempts to restrict their evangelistic efforts failed, the movement's ultra-orthodox opponents withdraw to illegal, violent forms of repression. They attempt to deprave the movement from a „politics of equal respect” (Taylor 1995: 77-89, Habermas 1995: 138-156).

Duyvendak points out that movements must neither fully nor always fit this typology (Duyvendak 1992: 21). Considering this flexibility, the studied movement appears to meet best the sub-cultural pattern of Duyvendak.

Secondly, for survival (Taylor 1995: 74, Appiah 1995: 179-182) the movement and its groups need the Israeli state to protect their religious freedom, as it does of other religious groups. Ultra-Orthodox opponents of the movement, assumingly Habad (Perlman 1994), appear to disapprove of general religious freedom for citizens and want to prescribe their religious orientation for all Jewish citizens. Given a democratic constitutional state, founded on the rule of law in Western terms (Habermas 1995: 140, 143), such aspiration must appear unacceptable. To some, there appears no sharp line between a politics of recognition and a politics of coercion (Appiah 1995: 186).

The conflict with the ultra-Orthodox falls not out of thin air. Following Saperstein (1992), also the Habad movement can be understood as a Messiah movement, since parts of it claim that the late „Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of Brooklyn, New York, was the Messiah” (Kjær-Hansen 1994: viii). Consequently, a movement that hails and propagates Jesus, whom Jews traditionally consider as abhorring Christian property, as Jewish Messiah, must „naturally” appear as wrong and as rival to Habad. In addition, large-scale evangelistic attempts from abroad caused Orthodox Knesset members to propose laws to criminalize evangelization and its means (Maoz 1998: 4-6). In March 1997, concerned Messianic assigned a committee to oppose these legislation efforts. It had to inform the Israeli public and internationally to ask Christians and governments' representatives to protest against legislation that appears to violate human rights and basics of democracy. Respondents reported that all Israeli rabbis received a letter from the rabbinate that obliged them to ask any immigrant if he or she considers Jesus as Messiah. In case of a positive answer they must deny immigration. At the founding of the Jewish nation, in the shadow of the Holocaust (Habermas 1995: 14), the promise was to have a homeland for any Jew, regardless the held world-view.

Today this appears not fully valid anymore, at least not for Jews who believe in Jesus as their Messiah, who insist not to be Christian, but still Jewish instead. Various respondents stated that

it seems, as Jew one may believe in the most ridiculous and un-Jewish things, as long as one does not believe in Jesus.

The ancient, bad relationship between church and synagogue appears to find here a contemporary expression in the denial of immigration to Jews who believe in Jesus as Messiah. Respondents reported that orthodox minority groups seek mandates to control immigration and working permits. In this context, since 1997, three „anti-missionary laws” got submitted to Knesset. Leaders and members of all four types of groups intend to break any such law if it should ever pass legislation. „Forbidding us to evangelize, is like forbidding us to breathe” (8/97). They are not willing to back down in the face of such a legislation, as they also perceive that it contradicts human rights (5/97).

In April 1999 the last of the three bills was removed from the table, as its proponent retired from Knesset. Unfortunately this event was parallelled by a series of arson against Christians and Messianic individuals and institutions. If usually the Israeli majority culture would be insensible towards the movement as not-respected (Habermas 1995: 147), exactly these violent attacks against the movement raise attention, sympathy and respect for it. In a liberal sense of neutrality, the Israeli authorities usually seem neither to forbid nor to foster the movement. Thus the state and wider public of Israel do not appear as opponents of the movement, but a part of Jewish ultra-orthodoxy appears as such.

Thirdly, support by overseas Christian and Messianic organizations appears still crucial for the movement's efforts. Moral support aims, for example, at preventing the proposed anti-missionary laws to pass legislation and especially to encourage individuals and groups that have been subject to violence by ultra-Orthodox „zealots”. Financial support helps, to finance humanitarian aid and institutions, to fight proposed „anti-missionary” laws by means of P. R., to maintain and to foster Israeli Messianic Jewish institutions, and to pursue evangelism. As non-Messianic and Messianic Jews have a strong sense for social responsibility, Christian institutions from abroad assign considerable means to Israeli humanitarian and cultural projects of non-Messianic and Messianic institutions. Respondents mentioned no unusual irregularities in relationships between Christian organizations and the ecclesiastical part of the movement.

Yet some Christian groups cannot appreciate the various expressions of the synagogal part of the movement. Besides general Christian anti-Jewish sentiments, especially the synagogal type expressions of the movement appear to displease those who believe that Christianity replaced Israel and Judaism, and feel therefore superior towards Judaism. Such churches disapprove of the programmatic and paradigmatic change that Jewish believers have themselves initiated for the survival of their Jewish identity (Greene 1998). To these churches, especially synagogal expressions of faith in Jesus seem to form a serious ideological threat, as they may have „disturbing implications for some Christian doctrines” (Weiner 1961: 114). By their mere existence Messianic Jewish synagogal expressions appear to question the claim of a lasting superiority and domination of the gentile church over Jewish believers, Judaism and Israel - the Jewish people (idem). It appears doubtful that a Christian opposition lastingly could hinder synagogal expression in the movement. It is as questionable whether ultra-Orthodox hostility can stop or dissolve the movement by normal means (Habermas 1995: 152-155).

To consider „the Notions of Trust, Reciprocity and Imagery” (Wels 1997) 41Quotes are taken from a draft that was not (yet) intended for quotation (Wells 1997: 21). ) can further enlighten the different relationships between external Christian groups on the one side and ecclesiastical and synagogal groups of the movement on the other side, and their social implications.

- Trust is a precondition for any reciprocal relationship and to fulfill mutual obligations. A reciprocal relationship requires actors to trust that their mutual conceptions of reality are sufficiently congruent to predict mutual behaviour (Wels 1997: 35).

- Reciprocity can range from unconditional over balanced to negative, and appears to run „parallel with the increase in social distance between „us” and „them” ” (Wels 1997: 27). Also in unequal reciprocal relations, for example between strong Christian and small Messianic groups, value is contextual, relative and situational (Wels 1997: 29). Trust and reciprocity, as intertwined aspects of social relations, can conceptually and theoretically be discerned but not separately observed and experienced.

- Trust and reciprocity are subject to imagery. Actors balance knowledge and ignorance about their counterpart to anticipate its behaviour. The labelling with „us” and „them” simplifies social complexity and uncertainty and symbolically creates, or even stipulates, a social distance, in which the other usually appears as morally less (Wels 1997: 36).

Christian organizations, which think Christianity has replaced Judaism, consider synagogal type groups of the movement from culturally poor and alien to theologically wrong, and consequentially as morally inferior. The more they consider themselves as supernaturally distinguished from „them”, the greater the social distance appears to them, the more difficult they find it to trust and not to aspire negative reciprocity, if they want a relationship at all. It happened that a foreign nationalistic Christian group purposefully spread lies about a synagogal leader. In another instance it appeared that a Christian group misled representatives of synagogal and ecclesiastical groups. Christian organizations that consider synagogal appearance as legitimate Jewish expression of faith in Jesus accordingly regard synagogal type groups ranging from culturally justified to theologically correct and genuine, as morally maybe even superior. The less they regard themselves as supernaturally superior to „them”, the more they perceive „them” as inclusively „us”. The smaller the social distance appears to them, the easier they find it to trust and to develop an even unconditional reciprocity. Whether the relationship, between ecclesiastical and synagogal groups on the one side and Christian groups on the other side, will be carried by trust and balanced or even unconditional reciprocity, appears to depend on mutual imagery.

Unconditional reciprocity appears occasionally based on the supernatural perception that blessing Jews will always be rewarded by the supernatural (Genesis 12:3). Altruism appears doubtful if based on such notions, while pragmatically it makes little difference for the movement and its parts. Where Christian groups used unequal reciprocal relationships to exhort their will from Jewish believers at the expense of their Jewish identity, it happened that the Jewish believers changed affiliation and decisively joined the synagogal view. Though numerically the movement is far inferior to Christianity, by means of „olive tree theology” (Stern 1991a: 47-60) some claim a supernatural and ancient superior status for it (Kjær-Hansen 1996: 7-18). The means to balance reciprocity on the Christian side seem moral and material support, and on the side of the movement insight into Jewish tradition and understanding of Scripture. Occasionally I got the unfortunate impression that while representatives of the movement appeared to believe that they had much to teach Christianity, they also believed that they had little to nothing to learn from it. If they aspire to be understood and heard, to be recognised, they will have to listen as well, to recognise.

I perceive the dichotomy of the relationship of Christian groups towards the movement, reflected also within the movement by ecclesiastic and synagogal expression, as particularly caused by different theological, supernatural perceptions about, the status of the Jewish people, Israel as a nation and Torah. Stern distinguishes two theories to comprehend the source of the conflict and offers a third to overcome it:

- „Replacement” or „covenant theology” (Stern 1991a: 46-47) depicts the church as the new, spiritual Israel that replaced the physical Israel, the Jews. From that point of view, Judaism and Israel appear at least as „historic anachronism” (Weiner 1961: 114), at worst as abomination whose right to exist appears doubtful. Christians that hold such views will treat Jews in general, and Jews who express their believe in Jesus in synagogal ways in particular, in an uncomprehending or hostile way (Stern 1988: 8, Stern 1991a: 70).

- The second, „the two-covenant theory” (Stern 1991a: 256-258), Stern sees as having originated within Judaism with Rambam. „Rambam” is an acronym for Rabbi Moshe Ben-Maimon, maybe better known to Christians as Maimonides (1135-1204). In contemporary times, Rosenzweig reintroduced this theory in his Der Stern der Erlösung. It infers, that gentiles can come to God as father only through Jesus, and that Jews are already with the Father through the covenants of Abraham and Moses. Therefore, they would not need Jesus anymore. From that view, Judaism appears equivalent to Christianity and evangelization of the Jews becomes unnecessary. In an „evangelical” movement such a view cannot find favour, as it sees Jesus as the Messiah of the Jews in the first place.

- The solution to the dilemma Stern sees in an „olive tree theology” (Stern 1991: 47-59), which refers to an allegory in Romans 11:16-26. The olive tree symbolises the Jewish people that grew from the roots of the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Jews who believe in Jesus, Messianic Jews, are natural branches of this tree. Jews who do not believe in Jesus are cut off branches. Gentile believers are grafted in branches, ever since called Christians (Acts 11:26.28, 1 Peter 4:16). The fast-growing gentile majority in the early church removed the Jewish and the gentile branches from another, until Jewish believers totally disappeared and a gentile body of believers remained, the Church (Schmidt 1965: 57). Until recently, the Jewish people and the church existed almost entirely separately. For Jews this reflected their ages-long bad experiences with the church. For Christians it reflected their assumed superiority over Jews, their ignorance about how deeply their faith roots in Judaism and their uninformed prejudices against Jews. To olive tree theologians, Christians and Messianic Jews belong together, and non-Messianic Jews have to be grafted in back again, until „the Jewish nation will have a believing majority and/or a believing establishment” (Stern 1991a: 57). Here arouses the conflict with the Jewish orthodoxy, and lingers a potential conflict with the state.

As for a theology of the Land Palestinian and Arab Christians appear important. Representatives of the synagogal view consider as solution for the current political conflict a peaceful coexistence of the two peoples in one land. They argue that Jews ever coexisted with other people in the „promised land”. Consequentially they developed reconciliation strategies with Arab individuals and institutions. The first important step may be to talk with one another and to learn to understand one another. This conversation takes shape, in local meetings between Messianic Jews and Arab Christians and Muslim, and in international and interdenominational consultations on a theology of the land.

Fourthly, the Israeli Jewish orthodoxy may appear necessary for the world wide Messianic Jewish movement's religious legitimation and recognition within Judaism and the Jewry. Though most Israeli may be regarded as secularised and as non-Orthodox in their praxis, it appears only few would religiously oppose orthodoxy. This appears as religious insecurity and dependence on Orthodox specialists for the sake of a Jewish identity. Besides Messianic Jews, also Reform and Liberal synagogues have an interest to enjoy their human rights in Israel fully (Weiner 1961). However, an extremist minority among the Orthodox appears fierce and physically violent in its disapproval of the Messianic cause, even dehumanising opponents. Over the last five decades extremists revealed a strategical behaviour to intimidate other faiths. First, they exerted physical and moral violence against individuals and groups. They placed bombs and blew up cars and houses. They attempted to burn and burned evangelical chapels and Messianic synagogues, also private homes and threatened to kidnap believers' children. In March 1999 a series of Molotov cocktail attacks took place. One devastated the house of a Messianic family. Another damaged a Baptist bookstore. The third was an attempted murder of a popular Messianic leader, by that endangering 28 other non-Messianic families living in the same flat building. At earlier instances individuals got beaten up and threatened with knifes. Worshipping congregations got threatened, so that the police had to rescue them from the assaults. After crude violence did not show the desired results, more sophisticated approaches were applied. Police and the military are said to have been challenged illegally to act against believers. Consequently police once illegally confiscated literature and safe-kept individuals. New proposals of anti-missionary laws marked a recent hostile climax. Already Zaretsky observed that Messianic Jews serve as „scapegoats”, whereas „the cry of „missionary activity” whenever a problem arises, often only masks bureaucratic difficulties that are totally unrelated to missionary work” (Zaretzky 1974: 397). Though extremists try to employ authorities against the Messianic, the authorities usually appear to protect them, to defend principles of democracy state founded on the rule of law (Habermas 1995).

While the movement has structural relationships with various Christian organizations, it appeared not to have comparable structural relationships with Jewish organizations. However, at least a varied fund and ongoing production of literature, tracts and academic publications, is accessible to all who would want to read it. Periodicals supply a theological platform to elaborate on Christian-Jewish issues. Messianic books, periodicals and tracts treat issues of concern. Only recently the first volume of a commentary on the Jewish roots of New Testament was published (Shulam 1998). Occasionally academic work contributes to the dialogue between the Messianic and other Jews. Recently, the Hebrew university in Jerusalem accepted a dissertation in Ivrit on the history of the Messianic in Israel (LCJE Bulletin 49 1997: 8-9). Messianic Jews repeatedly appeared on television and were discussed, yet also derogatorily denounced in papers. Some time ago for the first time Orthodox rabbis discussed with Messianic leaders live on televison. Messianic leaders regarded this as considerably unique, first public recognition from the side of the Orthodox. Until then they were publicly not acknowledged as conversation and discussion partners.

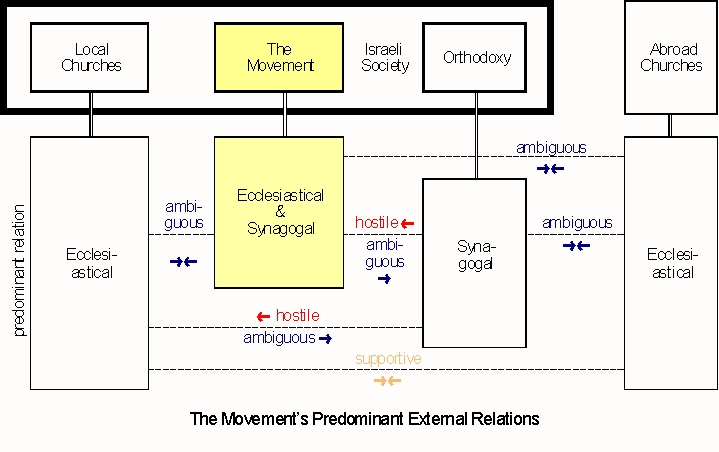

As for „contextual interpretation” (Van den Eeden 1994), the various external social structural relationships of the movement can be summarized and visualised in the following graph. For that it must be incomplete, simplifying the complex social reality of the movement. The graph shows neither all of the above considered relations nor all of their aspects. Still, it may help to perceive the movement in its wider external context.

the Current Israeli Messianic Jewish Movement

© Kalab 1999

The predominant ambiguous relation, from local and overseas churches towards the Messianic Jewish movement and Jewish orthodoxy, appears to stem from anti-Jewish sentiments within the churches on the one side, and from the synagogal expression of parts of the movement and the orthodoxy on the other side. Without any synagogal expression within the movement and the orthodoxy, the relation might be as supportive as between local and overseas churches. The churches appear not to accept a synagogal expression equal to an ecclesiastical expression. The ambiguity in the relation of the movement with the churches appears to depend on real and perceived, anti-Jewish sentiments and aspiration to dominate within the churches.

The predominant hostile relation of the Orthodox Jewry towards the movement and local churches appears to result from anti-Christian sentiments within the orthodoxy, in particular within the ultra-orthodoxy. The orthodoxy appears to refuse to distinguish between ecclesiastical and synagogal expression, and to regard any group of the movement as objectionable. The ambiguity in the relation of the movement towards Orthodox Jewry appears to result from the rejection of synagogal expression by parts of the movement. The predominant supportive relation between local and overseas churches and missions appears to express a mutual acceptance as equals. The Israeli society occasionally appears to sympathise with the movement against ultra-Orthodox dominance, exclusivity and violence. The authorities predominantly protect the movement.

After having strolled the plateau, examining familiar and unfamiliar traces of life, comparing considerable different appearances and expressions, the companion may want to procede to the vantage point, to relax and to contemplate some collected impressions.